2015 – two c-prints with audio guide

The story behind the photos you see here starts with a SS general during the Nazi period, who was also a great lover of art. Taking advantage of his position of power, he managed to acquire many works of art belonging to wealthy Jewish families.

At the end of the war he was captured by the Soviet army. Somehow he was able to escape, however, and to erase every trace of himself and of his personal war spoils: hundreds works of art, comprising sculptures, paintings, drawings as well as pieces of furniture.

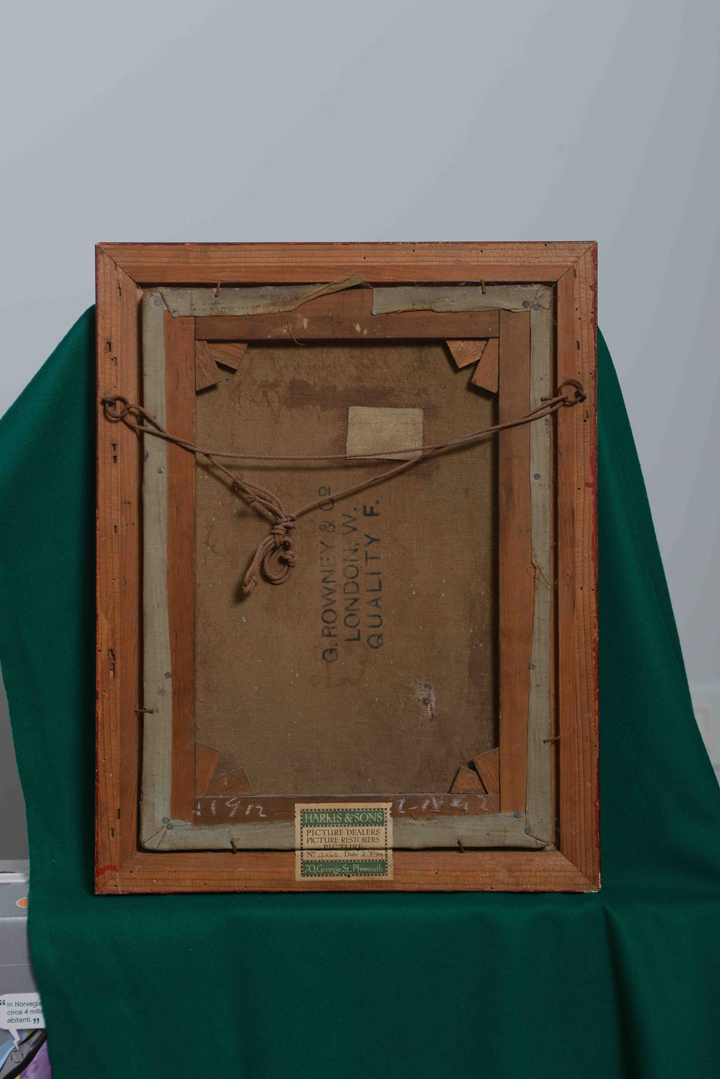

Among these was the painting you see presented here, known as The Man with the Pipe.

Several years later the general and his collection resurfaced in Rome, where he’d gone to live under a false identity. He occupied a very spacious apartment, which he’d turned into a kind of private museum.

Those fortunate enough to be admitted to the apartment – and there weren’t many – agreed that it was one of the most beautiful and invisible collections in the world.

One of these rare visitors was the daughter of Alfred Hitchcock, who, at the suggestion of a London gallery owner who had authenticated some of the general’s paintings, apparently tried very hard to get him to sell her precisely

this very same painting, The Man with the Pipe, but without success.

And then there was a young Italian woman, freshly graduated from the Roman Academy of Fine Art. The former Nazi officer and the young woman started seeing each other. He was fascinated by her beauty, she by the beauty of his collection.

Over the years they spent more and more time together. They continued seeing each other for years, until the German officer, in his old age, decided to leave the entire collection to the woman, convinced as he was by her promise, which she would never keep, to open an art gallery in his memory.

So when the general died, the woman inherited all his works of art, which she showed to a well-known Roman antiquarian with many connections in high society as well as in the underworld.

The antiquarian soon proved to have little scruple. He persuaded the woman to sell many of the artworks, nearly all of them, in fact, for prices far below their actual value, and ended up involving her in a scheme of false expert analyses that brought her into conflict with the law and ruined her reputation.

The woman decided to move back to the village in Southern Italy where she’d been born, taking with her the few artworks and pieces of furniture she hadn’t yet sold.

One of these was a 17th-century dresser which she’d always been very fond of. Before he died, the general had urged her never to sell it, saying it was hers to keep and that he hoped it would will bring her fortune, just as it had done to others.’

When the moving company arrived from Rome, the woman asked the movers to carry the dresser to the upper floor. However, it was made of solid walnut and too heavy to carry upstairs, so the movers decided to take it apart and carry it up piece by piece. As they were carrying up the drawers, the movers saw that one drawer had a false bottom. They told the woman, who asked them to open it to see if anything was hidden inside.

Wrapped in cloth was The Man with the Pipe, probably the only painting in the general’s collection the woman had never seen. Next to it there was a note describing how the general had obtained the painting through barter: the original owner, a Jew of Dutch descent, had been spared, together with his family, in exchange for the painting.

The woman, distrustful as she had become, kept the painting hidden for a long time, until she finally turned to a connoisseur of late 19th-century painting, an old friend of hers from the art academy, whom she asked to look at the painting. This friend, who also took the photos you see here, studied the painting extensively and despite an obvious scratch that made it difficult to read, found an inscription on the bottom right side of the canvas: a year, 1884, and above it four letters: V, I, N, C. Underneath the scratch he also found traces of three more letters: E, N, T. VINCENT